A Vibrant Story of Islam in Sudan Behind the Headlines

Many people don’t know the rich legacy of Islam in Sudan. Situated at the junction of the Arab and African world, Sudan is an amalgamation of centuries of changing powers and faiths. Far away from politically charged headlines, the country is home to a mix of old and new architecture from different chapters in history and a vibrant culture and Islamic legacy.

The shifting sands of the Sudan region have always been dynamic; the area has been overseen by pharaohs, Nubian kings, Ottoman rulers, and British forces, to name a few. These many periods of rule each changed the landscape and helped to shape the diversity of cultures and presence of Islam in Sudan. This unique balance of the traditional and the modern are what make up the fabric of the country today.

Soft Drinks, Ice Cream, and Shoe Polish – Sudan’s All-Purpose Gum Arabic

If you find yourself wandering down the street on a Friday morning, Sudan’s souks will be ripe with action. With sellers boasting a range of products, there is no better place to find local goods and craftspeople. From silver jewelry to carved candlesticks, fresh dates to aromatic spices, and house products to bright clothing, a grocery or department store pales in comparison.

But far away from the souks, you can find another natural product of Sudan hidden in your grocery aisles. Gum arabic is a hardened sap that is hiding in the ingredient list of many soft drinks, ice cream, and even shoe polish. It received its name from the Arab merchants trading and selling the product widely – another legacy of Islam in Sudan. Now, Sudan is the largest producer of this product in the world. Part of the widespread use comes from its incredible versatility. Herbal teas, natural beauty products, and even watercolours all use the processed gum.

But gum arabic also played a significant role in disseminating the words of the Holy Quran centuries ago. Many ancient Quranic manuscripts, even dating as far back as the 13th century CE, contain gum arabic in their inks. The calligrapher would prepare the ink by mixing the gum with other materials such as carbon to get the desired colour and consistency needed to compose the Arabic script.

Mosque of the Two Niles – A Tribute to Islam’s Heritage in Sudan

The architecture of Islamic tradition in Sudan is as rich as its history. The Masjid al-Nilein or Mosque of the Two Niles in Omdurman is situated at the confluence of the Blue and the White Nile. It was designed by architect Qamar Adawla Abd Al-Qadir Al-Tahir and features striking white keel arches holding up a large geometric dome.

But the beauty of Masjid al-Nilein is not only in its outward appearance but also in its position as a communal space — an example that was first set by the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ. In the time of the Prophet ﷺ, the mosque served not only as a place of worship but also as a political, educational, and communal hub. Often connected to the mosques were schools where students could study a wide range of subjects. The Masjid al-Nilein is adjoined with the University of the Holy Quran and Islamic Studies and is next to the National Council. The central location allows for the fostering of community and the upholding of pillars such as education, faith, and social/political voice which are rooted in the history of Islam.

Dr. Khalida Zahir — A Model for Women’s Rights and Education

Dr. Khalida Zahir, one of Sudan’s first female doctors, was born in 1926 in Omdurman. Her father was a staunch supporter of her education. When community members approached her father and objected to her studying in the company of men, he dismissed them by saying that “she was made from a different dough” and that he trusted his daughter completely. This trust encouraged Zahir to strive high, leading her to be only one of two women admitted that year into the Kitchener School of Medicine in Khartoum.

At this time, it was virtually unheard of for a woman to leave the home, let alone graduate from university, so Zahir’s accomplishment was symbolic in defining a new age for women’s education. But despite her academic success, she still encountered many challenges. When she went to work, she was frequently pelted with stones and needed to be shielded by others.

This hardship prompted Zahir to co-found the very first political movement for women: the Young Women’s Cultural Society and later on, the Sudanese Women’s Union. These organizations advocated for female workplace equality, literacy, and teaching girls to avoid superstitious beliefs. However, not all were fans of her progressive thinking. When she held demonstrations against colonial rule, she was subsequently arrested. Still, her spirit for activism never diminished and paved the way for others to follow.

Alongside all of her social work, Dr. Zahir was also a successful physician. In her career spanning over 60 years, she received diplomas in England having specialized in paediatrics, received an honorary doctorate from the University of Khartoum, and even offered to treat the impoverished without payment. Until her last breath, she fought tirelessly for women’s rights and was able to lay down the groundwork for others to follow her example. In the years 2000-2009, the proportion of female medical students increased by 69.5% at the University of Khartoum. She passed away at the age of 80 and her life dedicated to the service of others was commemorated with a procession in Khartoum.

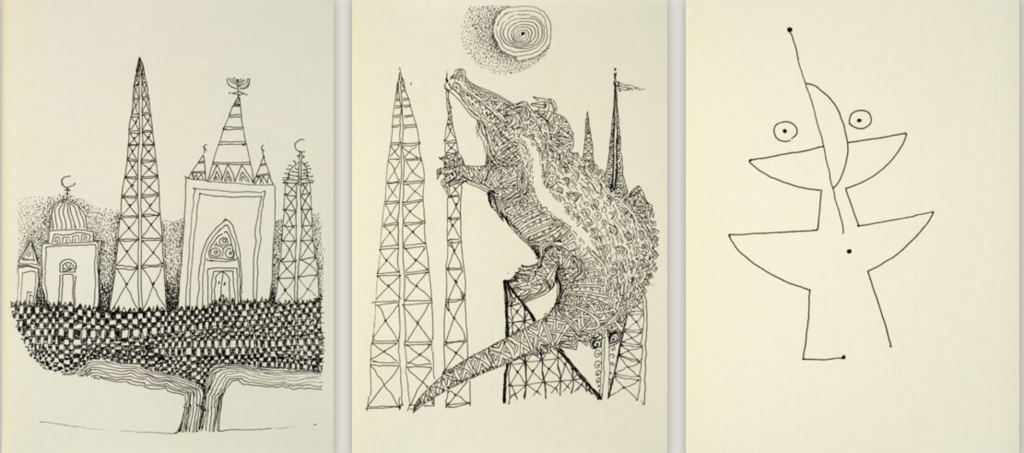

Ibrahim El-Salahi — Pioneering Sudanese Artist

Born in 1930, Ibrahim El-Salahi is one of Sudan’s most influential pioneers of African contemporary art. His first exposure to art was when watching his father — an Islamic scholar — drawing ornamental, arabesque designs on writing slates. This sparked his interest in learning art at the Gordon Memorial College in Khartoum. After studying on a scholarship in London, he returned to Khartoum and rediscovered the beauty of Sudanese Arabic script. He describes this reconnection: “I had to break the bone form of the letters to find out what they came from — animals, humans, voices, spirits.” The style of merging traditional Arabic calligraphy with the elements of modern art was a movement known as hurufiyya and it was developed by El-Salahi and other Sudanese artists during this time.

In 1975, El-Salahi had accepted a job at Sudan’s Ministry of Culture but the capricious political situation was about to turn his life around—El-Salahi was imprisoned for six months without trial. During this trying time he found deep solace in his faith and art where he would secretly draw on small scraps of paper that he buried in the ground. Years after his release, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City would acquire these sketches. He describes the process of creating the works as, “[taking] away the bitterness and humiliation of being incarcerated for something I hadn’t done. It is a Sudanese custom to forgive.”

Now at 90, El-Salahi resides in Oxford, UK, with his works showcased at various international galleries. But the years of experience can be seen in his series titled The Tree. The pieces are inspired by the English landscape with the trees similar to the variety that grows along the Nile in his homeland. The lines suggest an allusion to Islamic art styles, where the geometric shapes are used in tessellations to convey the magnitude and beauty of creation. These elements are what make El-Salahi’s work echo with deeper themes of pain, faith, and humanity.

Islamic Relief’s Presence in Sudan

Islamic Relief was first set up in 1984 to aid those suffering under the famine in Sudan. The people of Sudan face two major challenges; one is the longstanding conflict in the country which has led to widespread displacement and the other is drought and other climate-related problems. To address these we provide immediate relief like water and shelter, while working to find long-term solutions to issues such as education and improved livelihoods.

Currently, there is an acute need in Sudan with the Nile River rising to unprecedented levels due to heavy rains, causing floods, landslides and widespread damage. Your donations can help over half a million people affected by providing sanitation as well as emergency shelters and mosquito nets.

The villagers moving their belongings in a boat in flood-affected Wad Ramli, Khartoum.

Thanks to the outpouring of donations and support, Islamic Relief has provided services to those in need in Sudan and around the world. However, the looming conflicts and climate-change related emergencies do not just have quantitative effects. They also threaten to erode the unique history and the livelihoods of those that preserve it. By sharing Sudan’s story and the rich Islamic heritage of Sudan, while standing with the people especially those affected by tragedy, we can help ingrain these stories into our wider history.

This post is one of three in our series on Islamic Heritage Month. To learn more about the Islamic heritage of other countries where we work, read our post on the unknown history of Muslims in Sri Lanka, and stay tuned for the next one!